冠婚葬祭は、生から死、そして死後まで人の節目を映す。そのすべてにあるのは「涙」だ。作品に浮かぶのは100年前のイギリスのウェディングドレスと葬儀用ストレッチャー。何人がそこに腕を通し、何人が横たわったのか。その周りで流された涙はいくつだったのか。

涙はヒト特有の情動の産物であり、物質的には変わらぬはずの存在に、見えない「大きな変化」を感じ取る証でもある。

水槽に漂う抜け殻のドレスは「もぬけ」を体現する。かつて誰かがいた痕跡としての殻に、光や風、微細な粒子が触れ、空間そのものを立ち上げる。

私たちは死を涙なしに受け入れられない。だが、もぬけが揺蕩う光景に向き合うと、物質と精神が細やかに交わりすれ違う瞬間を感じる。希望と絶望が同居する荒波のなかで、人は新たな涙を流すのだろう。

久保田沙耶

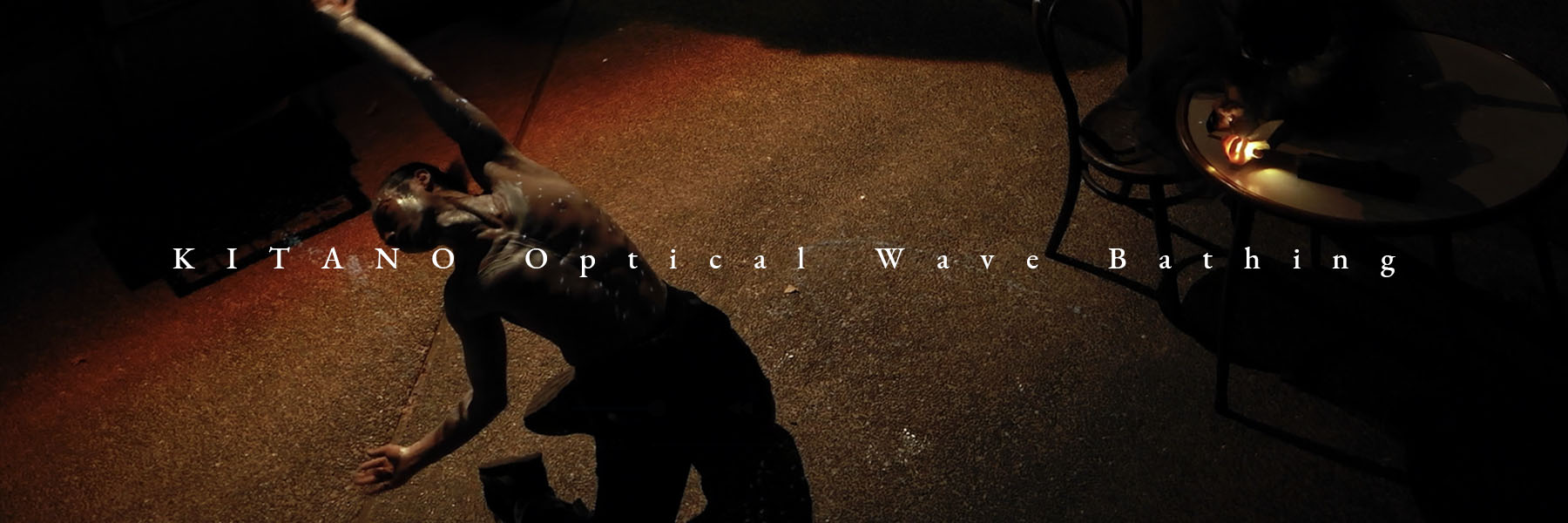

For each of the “Earth Room,” “Moon Room,” and “Sun Room” at Nagi Museum of Contemporary Art, we extended the works using light and shadow. At one point, xorium members joined a program called Jinsei Keiko and practiced Zen at Myōkōji Shunkō-in in Kyoto; by focusing attention on the body and accepting things with sharpened awareness, we felt consciousness spread into the space while the body remained, which made us question whether body and soul are separate and whether social rationality has conflated them.

Research into Nagi MOCA’s background revealed that the building was conceived around meditation and the liberation of bodily sensation, aiming to enable the self as a soul. The sensations from Zen closely matched our intent and became the basis for the work.

Nagi MOCA—created as a pioneering, third-generation museum where works, architecture, and the regional environment merge—commissioned us for its night openings. We therefore avoided a mere “nighttime spectacle” and aimed for an expression in which night itself generates new meaning for the works.

Out of respect for the “Earth,” “Moon,” and “Sun” works that remain with the building, we extended each through light. Light serves not only as illumination but as a medium to reexamine body–consciousness relations, restage each work’s domain, and provoke bodily awareness in the viewer.

Saya Kubota

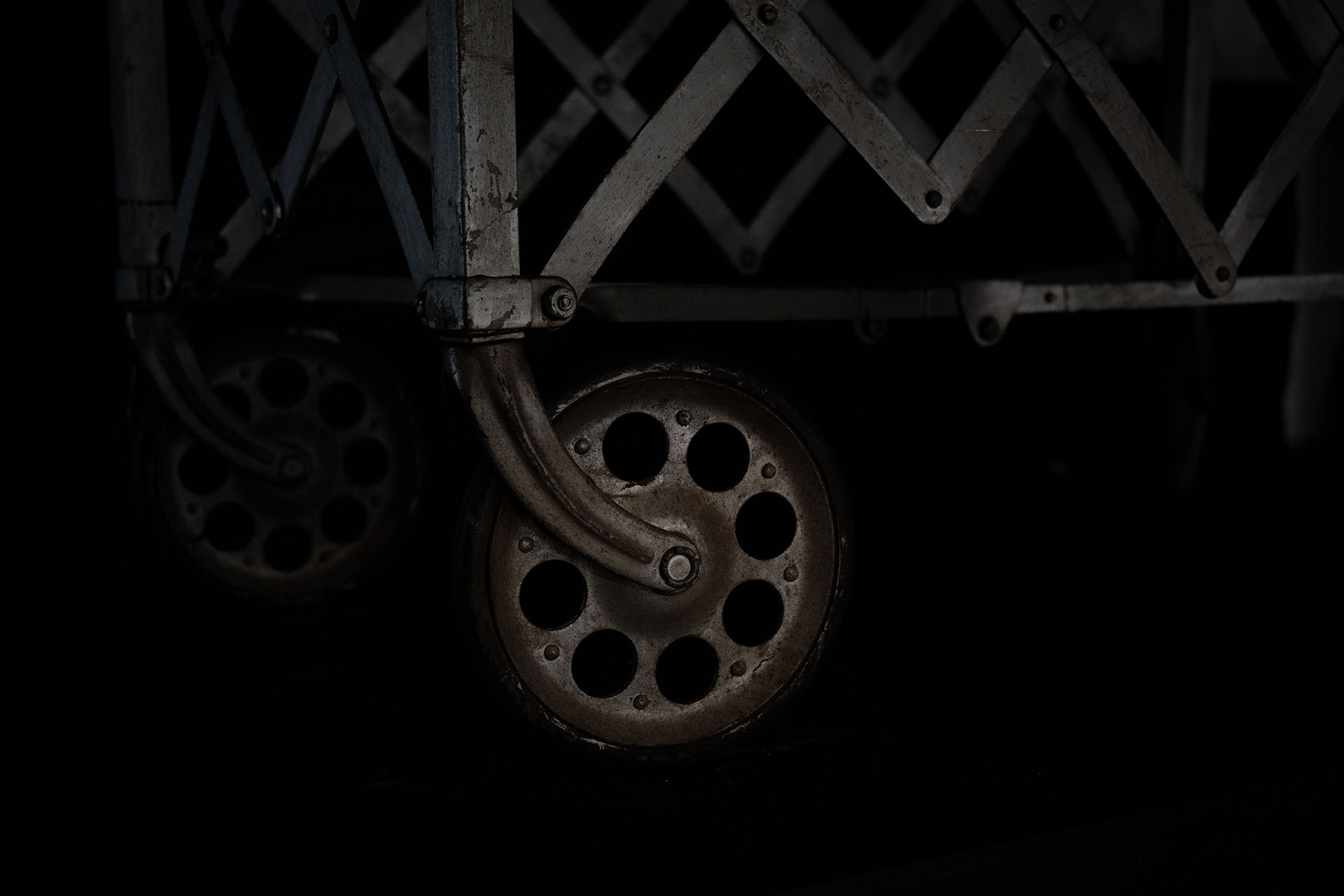

冠婚葬祭の四文字は、いずれもが人生の節目、および死後の扱われ方をさしており、人間が生まれてから死ぬまで、そして死んだあとに家族や親族の間で行われる行事全般をさしている。そのいずれも、思い浮かぶのは「涙」だ。作品の中に浮かんでいるのは私が以前個人的に購入したおおよそ100年前のイギリスのアンティークのウェディングドレスだ。そしてその空間を支えているのが、これもおおよそ100年前のイギリスの葬儀の際に使うストレッチャーである。何人の花嫁がそのドレスに腕を通し、何人の死者がそのストレッチャーに乗っただろうか。そして、彼、彼女たちを囲んだであろう多くの人々の涙の総量はどのくらいだろう。

涙には色々な種類があり、特にこの「喜び」や「悲しみ」といった感情が動いた時の涙は、ヒト特有のものであるとされている。「情動性分泌」と呼ばれる涙は、他の動物には見られない。この冠婚葬祭の主人公たる誰かが、人体、物質としてこの世に存在するという状態は冠婚葬祭のあいだ、変わらない。けれども人は涙する。その涙の本当の理由は、私たちの目には見えない「大きな存在の変化」を感じているからに他ならない。物質的に変化がなくとも、我々は常に変化の大海原にいることを心のどこかで知っている。喜びも、悲しみも、大きな心の動きがあれば、ある種の「ストレス」として人に涙を流させる。その「変化する存在」とは一体なんなのだろうか?

水槽の中にはクラゲのように、体が抜け落ちたウェディングドレスが浮かんでいる。まさに「もぬけの殻」。調べてみると「もぬく」という動詞があり、抜けて外に出る、脱するという意味で、古くは平安時代の万葉集でも使われていた。この言葉には「なにも無い」ということより「かつてここに何かが在った」ということが強調されている。この水槽の中には、花嫁たちと死者たちがい上にも重なりあいながらもぬけている。部屋に西日が差し込み、埃がキラキラと舞う時、はじめてそこに空間があるのだと認識するように、目で見ることのできない「もぬけている」その状態を認識するためにこの装置は制作された。一つのドレスの殻に、風があたり、光があたり、そしてそこへ微生物や埃、祝福のシャワーのような粒子が空気中にきらめき踊る。

私たちが、死を涙なしで受け入れることはおそらくできないのだろう。でも、もぬけがたゆたうこの水槽を見つめていれば、物質と精神は決して分離しているのではなく、たとえば細やかな霧の一粒くらいの大きさで、ささやき合い、混じり合い、すれ違っているのを感じる。アクチュアルに存在する人類の歴史のかさぶたのようなドレスとストレッチャーという物質に、見たことのないきらめきが、まるで物質を溶かすように行き交う。ノアの箱舟が嵐の中にいるとき、外はありとあらゆる騒音や叫びがあまりにけたたましく、逆に静けさを保っていたときく。この水槽にあるのも、ただの穏やかな凪の海ではないだろう。しかし、早すぎてゆっくりみえるようなこの荒波の粒子のうごきに、希望と絶望が手を取り合い、どんな別れさえも祝福できそうな気持ちになる。そのとき、人はどんな涙を流すのだろう。

The four characters of “kankon-sōsai” (weddings and funerals) mark the milestones of life and the ways we are treated even after death. They encompass the rituals carried out from birth to death and beyond, within families and communities. What comes to mind in all of these is “tears.”

Suspended within this work are two artifacts I once acquired: an antique English wedding dress from around a century ago, and a funeral stretcher from the same period. How many brides once slipped their arms into that dress? How many bodies rested upon that stretcher? And how many tears surrounded them all?

Tears come in many forms, but those born of joy and sorrow are uniquely human. Such “emotional tears” are unseen in other animals. The protagonists of these rites exist in the world as physical bodies, unchanged through these ceremonies—yet people weep. The true reason lies in sensing an invisible “greater transformation.” Even if no material change occurs, we know, deep down, that we are always adrift in an ocean of change. When the heart is moved deeply—by joy or sorrow—it produces tears as a kind of stress response. What, then, is this “changing existence”?

In the tank floats a wedding dress, its body shed like a jellyfish. A true “empty shell.” The old verb monuku means “to slip out, to depart,” and was already in use in the Manyōshū of the Heian era. The word emphasizes not emptiness, but the fact that “something once was here.” Inside this tank, brides and the departed overlap and drift as empty husks. Like when the evening sun streams into a room and dust glitters in the air, suddenly revealing space itself, this device was created to make visible the unseen state of “being emptied out.” Light, wind, microbes, dust, and particles like a shower of blessings shimmer and dance upon the shell of a single dress.

We likely cannot accept death without tears. Yet when gazing at the drifting emptiness, one senses that matter and spirit are never truly separate—they whisper, mingle, and cross paths, like droplets of mist. Upon the dress and stretcher, scars of human history made material, unknown radiance flows as if dissolving matter itself. It is said that Noah’s Ark, in the midst of the storm, maintained silence within precisely because of the overwhelming noise and cries outside. What exists in this tank is not a calm sea, but a turbulence that moves so fast it seems still. Within those particles in motion, hope and despair clasp hands, and even partings begin to feel like blessings. In such a moment, what kind of tears would we shed?

構想・コンセプト:久保田沙耶

制作:xorium

Concept & Planning: Saya Kubota

Artwork production: xorium

Other works

Copyright © xorium All rights reserved